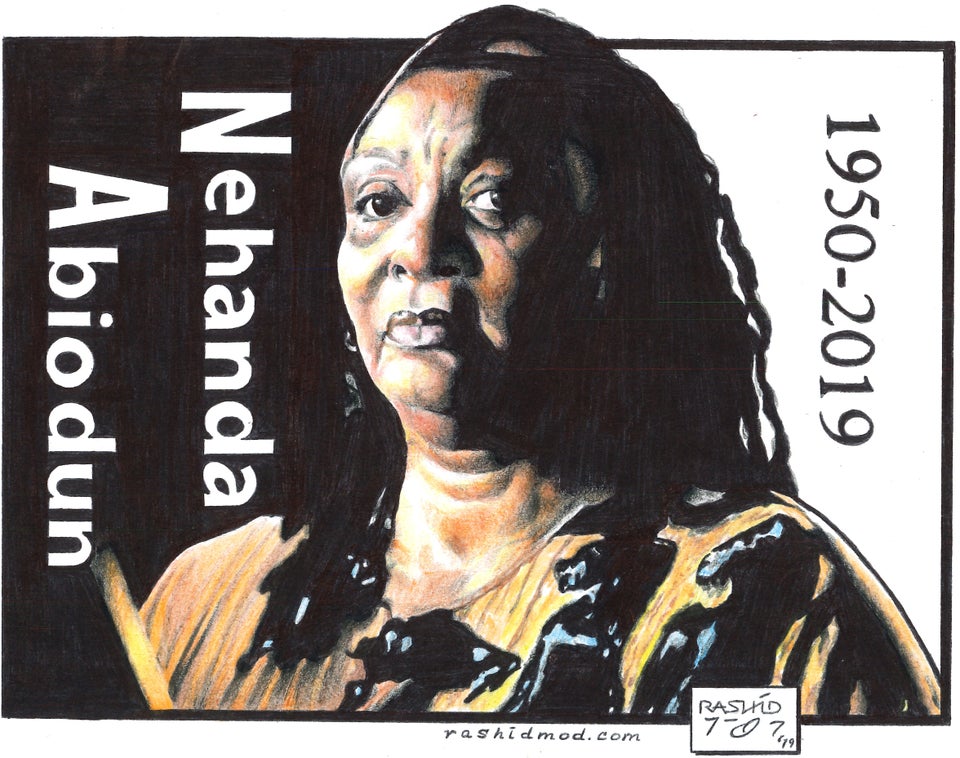

[Nehanda spent decades as a political exile in Cuba and passed on January 30, 2019 at her home in Havana. She is an important figure in the history of Dr. Mutulu Shakur]

Carry it on now.

Nehanda Isoke Abiodun, is a name that I am proud to have for many reasons. My first and last name were given to me by very close comrades on my 30th birthday and when Zimbabwe was fighting for its independence. Nehanda was a spiritualist revolutionary who lived in the 1800s and led the first war of liberation against the Rhodesians and I pray that I do her memory justice with my attempts to gain freedom for my people. Abiodun, means born at the time of war and for me was more than appropriate since New Afrikans (African-Americans) born in the Americas have been at war against those that have oppressed them for centuries. Isoke was a name given to me by movement Sisters in the early 1990’s here in Cuba and means a precious gift from God. I cried during the ceremony because it was a blessing to know that my efforts for our collective freedom was appreciated by my peers.

The Early Days

I was born in Harlem, New York, a child of the ’50s from parents who were of opposite poles politically. My father was a revolutionary Muslim nationalist, a disciple of Marcus Garvey and later Malcolm X. My mother is from the Martin Luther King school of thought, Christian, moderate and at that time an integrationist. They were both internationalist in their own ways and worked hard to give me the practical and spiritual wherewithal that allowed me to be proud as a woman and a descendant of Africa. They were also responsible for teaching me my first lessons on how to fight for what should have been inherently mine: human and civil rights.

As a Harlemite from the real old school and who grew up playing handball, double dutch and dodge ball, me and my crew, Betty, Dizzy Liz, Butch, Peter, Sarah and others from the ‘hood’ claimed as our patch of green pastures, Morningside Park. It was our haven, a place to escape the eyes of our parents, ride our bikes and just be kids.

In 1959 the City of New York and Columbia University agreed to build a gym in Morningside Park. The problem was that Columbia’s gym meant that kids like me who lived in the West Harlem community, the black part, would not have a place to play and our only admission to the gym would be through its back door and of course with their permission. There was also the pressing issue of Columbia and the city’s development plans which called for the demolition of a great portion of the buildings in West Harlem and the displacement of it’s residents. Though the gym issue is mostly associated with the 1968 student strikes at Columbia, the struggle to stop the building of the gym started in the early ’60s when community protest among residents who lived in the Morningside Park area.

Gettin’ Active

My activist career started with those same community protests at the age of 10. Without either of my parents’ knowledge, I joined the picket lines to save my park; racism and gentrification had nothing to do with it, my motives were purely selfish (Where were my friends and I going to play?), but an act that was to become a springboard of learning for me about the value of community organizing, self-determination, the power of unity among like-minded forces and nation-building.

It wasn’t hard for me to make the leap from being a casual 10-year-old protester to a community organizer. The lack of interest and total disdain among many of the teachers towards both students and parents in the schools I attended, the deplorable conditions that we were subjected to live under in Harlem, the rise of drug addiction, lack of health care, the subtle but affective racism that stifled the creativity of Black and Brown people in the North, coupled with the daily televised brutality against those who were fighting for civil rights in the south were the events that motivated me to become a volunteer and eventually part of the paid staff of the West Harlem Community Organization (WHCO).

During my tenure at WHCO I became more politicized and aware of the fact that no matter how hard we as an organization worked within the confines of the regulations and guidelines mandated by private and government funding agencies, our efforts for the most part were in vain. I came to know that to change the quality of our lives, it would take more than renovation of dilapidated tenements and band-aid remedies. The social ills that we experienced existed not by accident but by the design of those who ruled and profited from our labor.

What I was beginning to slowly understand were those speeches and lessons I heard first at home and then from Malcolm who I was privy to hear speak while he was a Minister for the Nation of Islam. Those lessons spoke of the need for a revolution, a socialist revolution that would bring about a change in a corrupt country, whose system of government was rooted in oppression, genocide, sexism and racism. What I was coming to grips with was that even though I was born in the US, an industrialized developed country, my community and those communities across the country like mine, lived in conditions that in some cases were worse than communities in the most impoverished nations in Third World countries. It was becoming increasingly clear to me that the Black nation was a colonized one within the borders of the United States.

Even though I was becoming more politically aware of the need for a different form of government in the US, for years I tried to work within the system, only to be more disillusioned as time went by. A seemingly endless chain of events like the increased US aggressions against Vietnam; the FBI’s and other police agencies’ attacks on progressives; the murder of Fred Hampton; the arrests of many activists across the country on trumped-up charges; increased heroin addiction in Harlem; the killing of a 13-year-old unarmed male black child by a New York police officer who claimed that he had a knife; the killing of a 5-year-old black baby by the LAPD; were only a few of the events that were forcing me to make some serious analysis about how I would make contributions for change.

When I left Columbia University I started working in a methadone clinic in East Harlem. Like many others at that time I thought that methadone was a viable clinical solution to heroin addiction. Eventually I was fired from the clinic for refusing to increase the dosage of one of the patients who had successfully stopped using illicit drugs and decreased his methadone intake from 120mgs to 20mgs in a very short time. It was the opinion of the clinic owners that I had lowered his methadone dosage too quickly. My defense was that the patient was no longer using illicit drugs, was not complaining about any physical discomfort and was functioning well in regards to his outside responsibilities. The ultimatum from the clinic owners was either increase the dosage or be fired. I opted to be fired rather than force a patient to take more drugs than was needed.

Lincoln Hospital Detox

After being fired I started investigating other alternatives to drug detoxification. It was this investigation that led me to Lincoln Hospital’s acupuncture drug detoxification clinic. Founded by activists who were either active or former members of The Black Panther Party, The Republic of New Afrika, The Young Lords and Students for a Democratic Society, the clinic successfully treated thousands of alcohol and drug-addicted people using acupuncture. Much of their success had to do with a comprehensive holistic medical treatment plan coupled with political education classes and community work that the patients were required to participate in.

The political education classes allowed the patient to understand his addiction in a more political context, how addiction contributed not only to the deterioration of his/herself, but the family and community as well. It was in those classes that they learned about the CIA’s involvement with heroin trafficking, using the body bags of dead soldiers killed in Vietnam to transport the drug. They also learned how drug addiction has been used as a deterrent to progressive movements nationally and internationally.

The community work they were asked to participate included such task as helping an evicted tenant find housing; welfare rights work; helping a family with transportation to go see an imprisoned relative; or attending a trial showing support for one of the many political prisoners who were being railroaded into prisons for their political work.

The educational classes and community work were important elements to the patient’s healing process because it allowed the patient to understand their oppression in a global sense and instead moved the patient from being a parasite to now contributing to the well being of their community.

Lincoln Detox ceased to exist as a revolutionary community-controlled health center when over 200 members of the New York police department and their SWAT teams used excessive force to close it down. Their official reason for doing so was the mismanagement of funds, but their real motive was revealed when Mayor Koch said that “Lincoln Detox was a breeding ground for revolutionary cells.”

The 20 years of community work that I participated in up until that time, the continued violence of the government and white terrorist hate groups against those who used peaceful means of protest, blatant police brutality against people of color, the ongoing arrests and assassinations of political activist by city, state and federal police agencies, along with the murderous international policies directed towards liberation movements and the colonized nations within the US borders were the dictates that lead me back to what were the roots of my political education; self determination and self defense for the Black nation.

Nehanda Goes Underground

In 1982 a federal warrant was issued for my arrest for violating the Rico Racketeering and Conspiracy laws. I choose to go underground for political reasons and while living clandestine I learned how important it is to struggle from a position of love and not hate. It was the love of humanity, freedom and justice that were the dictates that led me to where I was then and the love given from comrades that kept me mentally and spiritually healthy when I thought that I would die from a broken heart because of being separated from my family. And be assured that it is that same kind of love that has given me the resolve to continue daily in our quest for freedom. I recognize how blessed I am to have so many beautiful people in my life that genuinely care for me, individuals who are willing to make the sacrifices needed to carry on the traditions of principled struggle.

An Excerpt from “Life Underground” By Nehanda Abiodun in BLU 9

In the past I’ve resisted writing what it means to be underground, using security as an excuse, not wanting to give my enemies any more information than they already had. But I was fooling myself. The real reasons I didn’t want to take on the task was because it meant looking honestly at what my being underground did to some people that I love; that I had to relive some painful moments; and that I had to finally find out if I had forgiven myself for my errors as well as the hurt that my decisions had caused others. I cannot write about underground in a technical or theoretical way, I can only write about the cause and effects as I lived them.

Life in Exile

There are those who might feel sorry for me, being in exile, separated from family and friends, they shouldn’t. I made certain choices in my life and those decisions came with certain consequences. My only regret is the pain that my family suffered. Those of you who have children I’m sure can understand the hurt in my heart and guilt that I go through for leaving them. Fortunately we are healing as a family, them loving me unconditionally as I love them; so once again I am blessed.

Having not been able to yet meet my granddaughter, hug my children or my mother when I want, thinking about my comrades in prison and how much we have to do so they and we can be free are things that make me sad.

Nehanda Still Smiles

What makes me smile is a very long list. Listening to my 7 year old granddaughter tell me her definition of the word awesome, knowing that my mother is the radical dissident resident in her nursing home (you gotta know Large Marge to understand); my daughter’s stories about her brother; thinking about Mutulu in the clinic years ago doing the ‘Whip It,’ Chinganji’s ‘Lucy moments;’ Featherdance’s wedding; Jafari’s unending patience with me; young people who think I have all the answers and me knowing that I some times don’t even know the questions; Catherine dancing on the table last new year’s eve. Mari writing me and telling me of her recent marriage, her being at peace spiritually; Dana’s face when in moment of forgetfulness, calling me a fool (it was all good, she forgot I wasn’t her peer, we were in girlfriend mode); a baby’s smile and a vivid sunrise are just some of the things that make me smile.

The Role of the Intellectual in Liberation

I see no difference in the role or responsibility of an intellectual than I do a day laborer when it’s a question of freedom. Everyone has some sort of talent or intellect that would be of value to our liberation. It’s a question of finding out what talent we have to offer and giving it unselfishly to our struggle for self-determination.

Is the intellectual any more important than the person who organizes the people to understand the theories of the intellectual or the person who defends the protest and rallies or for that matter the person who does childcare so that parents can attend the demonstrations? Was it not the house servant that secured information about the master’s movements and plans that enabled various slave rebellions to be of some success? If we look at Cuba as an example we will see that their triumph was in part due to the fact that women and men from all sectors of the society made contributions to defeat Batista and no one has been excluded, regardless of education, race or gender from defending the revolution.

If you’re a writer, write about the revolution; if you’re a teacher, teach revolution; if you’re a painter, paint the scenes of freedom; if you’re a computer specialist, design the leaflets; if you’re a community organizer, organize the next rally; if you’re an MC then rap about Kwasi Balagoon, Sandra Pratt and Mtayari Shabaka Sundiata. There’s a job for everyone and no one who is willing to make an honest contribution should be turned down or discouraged from doing so or made to feel that what they donate is not needed or appreciated.

Intellectual Influences

There were many people who contributed to my political development. Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Fanon, Phoolan Devi, June Jordan, DuBois, Robert and Mabel Williams are a small fraction of the intellectuals who have influenced me and are probably familiar to most, but there are a number of political theories and opinions written by lesser known intellectuals who have contributed to my political consciousness. I’d like to think that my development is an ongoing process and have opened myself up to learn from many sources.

Political prisoners, Dr. Mutulu Shakur and David Gilbert, provide in-depth analysis of both current events and the past victories and errors of the Black Liberation Movement and the role and participation of the white radical left respectively. I am very grateful for the writings of women like Audre Lorde, bell hooks and Angela Davis for their theories regarding feminist thought. Drs. Adewole Umoja, Jafari Allen, Mukungu Akinyela, Akinyele Umoja, Sisters, Kathleen Cleaver, Assata Shakur, Marilyn Buck and Afeni Shakur have also been very important to my learning process.

I learn a great deal from young people whom I’m fortunate to have in my life. I’m honored that youth from both the US and Cuba have embraced me, opening their hearts and allowing me to enter their lives. Their energies have often been the fountain that I draw from to revive my commitment to struggle.