This paper is a response to questions and concerns regarding the 2010 “Discussion Paper” of the application of a Truth and Reconciliation Tribunal that addresses the conflict between the civil rights/black liberation struggle against the U.S. COINTELPRO low intensity warfare.

This paper is a response to questions and concerns regarding the 2010 “Discussion Paper” of the application of a Truth and Reconciliation Tribunal that addresses the conflict between the civil rights/black liberation struggle against the U.S. COINTELPRO low intensity warfare.

There are some among our ranks who have raised some legitimate and novel questions and concerns as to why I have chosen to espouse the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) process. I do this to shed light on, and to gain relief for, our political prisoners and allies of the black liberation movement. Below, I will endeavor to address some of the questions and concerns.

1. The people in South Africa had/have serious problems with the TRC put together by the ANC.

2. The people in South Africa believe that the national leaders sold them out by allowing their names to be used as the ones that were heading up the commission.

3. The people in South Africa believe that the illegal regime used the process to absolve the state apparatus of its complicity in crimes against humanity and to circumvent judicial review under the International Court in The Hague.

4. The people in South Africa believe that the Africans/Blacks would be, and were the only, ones telling the truth.

It’s important to acknowledge and understand that activists in our movement, who have made an effort to build support for political prisoners and prisoners of war in the U.S., have utilized and exhausted all available avenues that were open to them to gain relief for our freedom fighters.

We should understand that a process that gains relief for our freedom fighters should naturally contain the memorializing of our rich history of our contemporary resistance to the repressor’s racism, economic apartheid, etc. This history is important for the present generation of activists who seem to have no notion of the countless and enormous sacrifices that were made to pave the way for their present condition.

We must address the prevailing amnesia, and we must be successful in our earnest endeavor in the development of a mass base that through its will and organizational accomplishments, usher in a victory that accepts the existence of New African Freedom Fighters.

The false equating of our freedom fighters, political prisoners, and prisoners of war to so-called terrorists must be vehemently combated, for we are not terrorists! The government has won the battle of molding and shaping the narrative that those of us who dare to resist oppression, without passing go, are terrorists. Terrorism is just another method of resistance, which should not as it exists today include New African Freedom Fighters and our armed resistance to oppression here in the U.S.. It’s important to understand the effect the oppressors’ propaganda has had on the normal activist’s willingness to become engaged.

The word terrorist, unlike communist and fascist, is being abused by the oppressors as it disguises reality and impoverishes language and makes a banality out of the discussion of war, revolution, conflict, and politics. As Christopher Hitchens once said, “It’s the perfect instrument for the cheapening of public opinion and for the intimidation of dissent.”

A process that is developed on a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and/or the tribunals, has been the model used around the world. It allows for open discussion on the issue of resistance versus the state; it allows for a definition of terrorism that does not criminalize legitimate forms of resistance against oppression. It equally provides an avenue for healing and rebuilding, or at the very least, it provides a starting point post-conflict.

South Africa has no monopoly on the TRC process. The process has been accepted as a resolution process around the world. Furthermore, the TRC process is in fact an incomplete recording of the conflicts to which it has hitherto been applied.

It’s undeniable that our objective condition has more in common with the South African condition than most others. It’s important that our “think tanks” truly do an objective study of the TRC application process to be more precise as to its application to our struggle and situation. In terms of the special nature of our conflict, the Ireland application of a TRC and the Chilean application of a TRC combined could be transformed into a TRC that exactly fits our needs, but even then it will still not be a perfect fit.

A TRC process could not vet the New African/Black civil rights conflict, and our engagement must not presume that such a process will resolve 400 year odd years of conflict, or totally memorialize the aspect of armed resistance missing in the present Black history.

There is no question that to ignore the victimization of the vast majority of our people would be a recipe for the escalation of enmity between the races, and especially with the rise of the tea party in 2009 with its racist motto “we want our country back,” and its racist anti-Obama agenda.

The President of Chile in 1990 allowed for the creation of a national commission that was based on the principle of the TRC model. The process in Chile was politically fashioned to limit the inquiries into only those individuals who had disappeared. The President of Chile steadfastly resisted the disclosure of the names and ranks of the perpetrators who had committed countless human rights abuses. In Brazil, the TRC included no criminal charges against the military junta but it eventually provided the path for freedom for a female guerilla that became president of the country.

It is important that our researchers not limit our method of the application of the specific process, and rather we should become innovators in creating a process in substitution that addresses our own reality.

Our history during the Civil Rights/Black liberation Movement for Black people that was waged against the backdrop of the low intensity warfare director by J. Edgar Hoover’s counterintelligence program must be memorialized through a process.

The moral difficulty in pursuit of justice will be task driven, to the transition from domestic legal tactics to international application of justice based on the principles of international legal standards. The essence of justice is the universal principles applied nationally and internationally.

Certain applications of the TRC have granted blanket amnesty in all circumstances to the state forces, civilians, and combatants to ensure peace throughout the country.

Yet, other applications of the TRC have prosecuted violators of human rights abuses, and those who took up arms and opposed the perpetrators of said abuses. Some commissions conducted investigations and applied amnesty on a case-by-case basis. Some of the findings of the commission were even revealed to the public and even more hearings were conducted in public forums. Some countries have even provided for the victims and the families of human rights abuses.

Many governments and leaders of the international body claim to have helped to bring about the end of apartheid in South Africa after many, many years of neglect and supporting the atrocious behavior of the illegal regime. However, their failure to support resolution after resolution in the UN and other international institutions of persuasion were based in large part on those governments and leaders’ unique relationship with the U.S.. Needless to say, many lives were lost while the world staunchly supported that illegal regime.

The U.S. after many, many years of contradictions did engage with the international negotiations to end the racist regime in South Africa and institute a process to address the bitterness left from decades of internal conflict.

In South Africa the United States accepted and encouraged the TRC as a process for internal conflict resolution. In the United States, this government should also see the justification and applications of the same type of process to address the years of Jim Crow segregation and the apartheid era here in America as essential to ending the conflict in a peaceful manner.

Objective:

To have a national and international body. To conduct an equitable and unbiased investigation into the infractions and violations of the U.S. Constitution and U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights perpetrated by official organs of the U.S. Government under COINTELPRO (in regards to what is often referred to as “low intensity warfare,”) and to take the imperative steps to formulate and conduct official hearings and investigations under the auspices of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). A model similar in structure only to the TRC established in the Post-Apartheid South Africa era which applied the modern international standards “explicit means” of resolving international conflict(s).

(A) The status of those who have been identified by popular opinion as political prisoners and prisoners of war, imprisoned on U.S. Territory, in the aftermath of the civil rights/Black liberation struggle; and, as it pertains to the granting of amnesty and their unconditional release: And,

(B) Whether or not the liberation struggle was a legitimate revolutionary movement in accordance with and defined by the U.N. General Assembly Resolution #3103 and ratified on December 12th, 1973 and protocols 1 and 2. Additionally, if “our” political prisoners and prisoners of war satisfies the standards of the Norgaard Principles.

Goals:

1. To develop a process to conduct official hearings and investigations under a commission with a twofold purpose:

(A) To demand the establishment of the TRC under authority of the U.S. Congress, and

(B) To garner the endorsement and active support of various NGOs along with the support of the U.N. General Assembly and Security Council Member Nations. To apply international pressure to try and persuade the U.S. Government to take an active role in a TRC established under the authority and supervision of The Office of the U.N. High Commission for Human Rights or an agreed alternative.

2. Establish an exploratory committee from amongst restorative justice practitioners.

3. Solicit the assistance from those South Africans who participated in the Truth and

Reconciliation process that was conducted in their country, and the esteemed black and white advocates from North America’s struggle.

4. Request assistance from the South Africans who participated in the TRC process in their country to help develop a process and a step-by-step strategy for applying the TRC process to address crimes against humanity that was committed by the U.S. government against people of African descent who were forcefully abducted from the land of their birth. In addition to the matter of amnesty and the unconditional release of all political prisoners and prisoners of war being held in the U.S. prison system as a consequence of their political activities in which they engaged as a direct response to the acts and policies of the U.S. government which they viewed as crimes against humanity and peoples.

5. Appeal to and solicit the assistance at the local, national, and international levels of Black/New African politicians, in addition to high profile media, artists, and others of influence. To present and explain the narrative(s), outlining the process demanding freedom for our political prisoners and prisoners of war, as well establish an accurate record of “our history” of resistance and sacrifices.

6. Organize a viable grassroots public-awareness campaign in order to promote and explain the idea(s) for the need of a TRC which shall maintain and keep the focus of the issue at hand and others of importance at all times on the front burner. The grass root campaign should be that of a collective broad-base of networks, comprised of the various political prisoners and prisoners of war support committees, progressive experts, local, national, and international organizations and their affiliates.

It is important to build a base amongst its political prisoners (P.P.) and prisoner of war (P.O.W.s) support groups. Our challenge is to distinguish between a strategy pursued by most political prisoner-P.O.W. support and defense committees to achieve amnesty through a COINTELPRO hearing and the development of the Truth and Reconciliation Tribunal confronting the U.S. government’s low intensity warfare against the Civil Rights/black liberation Movement.

The strategic view in my opinion would be that a COINTELPRO hearing will assist in creating the political climate in which the Truth and Reconciliation Commission could be established with the focus to resolve past atrocities by giving voice to the forgotten survivors, combatants, and allies on toward to a peaceful conflict resolution by a means of an alternative dispute resolution mechanism.

The pursuit of COINTELPRO hearings, as to the disclosure justification process, has a much longer activist history. In some cases legally, and to a smaller degree politically, it is understandable why veterans of human rights forces feel mistakenly that the COINTELPRO and TRC are interchangeable. My argument is that they’re interrelated, but not interchangeable.

It is my position that the COINTELPRO commission format is not a process in it of itself that requires both conflicting parties to be revealed, rather our movement simply presents to the public. Hopefully with the process of the Freedom of Information Act, political information and testimony retrieved from the Freedom of Information Act process will pertain to the abuse by the state against the targeted group with no political agreement or incentive for the abuser to be forthcoming.

The Truth and Reconciliation Administrator of the tribunal on the U.S. government’s low intensity warfare waged on the Black liberation/Civil Rights Movement, including the COINTELPRO era, should be able to do the following:

(A) Provide the retention of past history of political and legal advocacy for human rights on a national and international standard of law.

(B) Possess the ability to articulate the distinguishing concepts of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission unique to the United States and the African population.

(C) Possess familiarity with various think tanks and intellectual associations within higher education historian societies that can help build the narrative for the alternative dispute process such as the TRC in the United States.

(D) Believe in the benefit of the TRC’s ability to achieve a sufficient documentation of human rights abuses during the period identified as the civil rights/black liberation/COINTELPRO era.

(E) Possesses proven ability to build administrative predictability in staff and operational infrastructure, providing a process that builds on various resources and skill sets that already exist.

(F) Possesses the ability to navigate among friendly and adversarial media outlets, in addition to being comfortable with information technology and social networking.

(G) Direct the development of a “New African” policy initiative lobby that helps to create the narrative and political opportunity that generates within the electoral process the policy that envisions the TRC demand for a COINTELPRO hearing that will assist in creating the political climate in which the Truth and Reconciliation Tribunal or Commission could be established with focus on a peaceful conflict resolution.

It is true that post-9/11, the reemergence of the same tactics disclosed through the Church Committee of COINTELPRO (in the early 70s of COINTELPRO) demonstrated that in many cases some of the same political prisoners, prisoners of war, and anti imperialists in U.S. prison again remain targeted as enemies of the state based on the conflict in the past which applied low intensity warfare to prevent the rise of a “Black ‘Messiah’” as directed by then director of the F.B.I. J.E. Hoover. This highlights the distinction between disclosure and resolution as it distinguishes the role of COINTELPRO hearings from the TRC hearings.

In the 1970s, we founded and directed the national task force for COINTELPRO litigation and research to increase public awareness of the F.B.I. counterintelligence program within the infected organization of the New African movement at a time when few were informed of its existential tactics, strategy, and effects.

It is one thing to make the point that many organizations and individuals of the black liberation era are still oppressed in what is advertised in the world as “the most free society.” Yet it is much more difficult to lay out the continuous cause of that oppression and the way in which it is perpetuated while identifying a process that addresses the direction that ends in the desired result. This desired result would be an alternative dispute process that is empowered to grant conditional amnesty, in addition to being charged with the duty of uncovering the truth about certain historical events.

In this respect our objective can adopt from the South African Truth and Reconciliation Committee (SATRC) model as to the infrastructure by developing two parallel objectives:

(A) Human Rights Violation Committee: These would be hearings in which survivors tell their “narratives” and “experiences.”

(B) Amnesty Committee: These would be hearings in where the accused (both from the state and the movement) come forward in the hopes of being granted amnesty and prove that their deeds were both politically motivated and proportional.

The controlling rule is that transparency will play a major role that will allow all parties to see the process and have their opportunity to bring forth their perspective and experiences. This process will allow for the feel of legitimacy while following the above (A&B) objectives. In this era of social media, there exists the ability to give a broad segment of the generations of the civil rights/black liberation era the capability to interact with and distinguish the U.S. TRC process from the 38 other TRCs held around the world. The SATRC were very vested in the public knowledge of their process and testimony. Although the weakness of the SATRC, after 17 years and about 90 books on the subject, is that the written report is still not available to the mass of South Africans, Azania. It has been the understanding that the documents only cost about $300 and the public record is controlled by the Justice Department and is still being withheld. This pitfall must not be allowed to happen in our process.

On the contrary, we want an informed public debate to advance the discourse in both reports (A&B) and their application of transitional justice, a comparatively new invented tradition of the twentieth century devices as a way to cope with the past and present internal conflict in the systematic violation of human rights.

A truth commission is a new class of international law that creates a new paradigm in the field of transitional justice in that it is designed as an alternative to trial with the rule of engagement based on negotiations between a state’s internal conflicting parties, in some cases applying existing international instruments, in other cases not so much.

The era of the hearing to be addressed that is manageable is a strategy for the broadest of support for several reasons. The testimony of acts in question remain in the realm of justice denied in the collective consciousness of our people. It also encompasses transition in tactical use by the state as well as the tactic for the Commission, Human Rights Violation Committee, as well as the Amnesty Committee. Finally, the documentation of the process is focused enough to warn conflicting parties of similar signs in the future to circumvent past oppressive behavior.

A truth commission in the United States that would cover 1950-1995 will cover 45 years. Between the overlapping timeline would be the optimal targeting periods of the Committee of UnAmerican Activity, the J.E. Hoover COINTELPRO, and the Church Committee findings.

The most important distinction between the SATRC and the U.S. government hearings is that there was no identifiable transition period that signaled the end of the era reflected by the above strategy disclosure in the South Africa hearings. The phase began in 1960 for the SATRC and terminated in 1995.

There is no way that our desired targeted period could encompass the breadth of the human rights violations and crimes against humanity by the United States. It is important however that whatever period we cover encompasses the period of the Civil Rights and Black liberation Movement period. Why? Because the survivors and participants of that generation who were activists (as as well as the perpetrators of the states) are available to provide the history as such to establish the patterns of the abuses and the rationale for their method of resistance that need be memorialized to saying nothing of the need to provide amnesty for the political prisoners and prisoners of war who still remain imprisoned after all these years.

The limitation of the present law in realizing a need for providing a process for conflict resolution only helps to prolong the human rights violations of charged freedom fighters in contrast to post-9/11 laws, be they international law or domestic law, have been manipulated in order to render a whole class of prisoners without an identifiable legal process that applies even to the minimum protection of the U.S. Constitution that considers it a right to at least provide the accused a process. So it’s clear that the state will alter laws and process to address different stages of conflict.

Let’s consider the political trial during the period between 1960-1996. The accused of our movement while fighting for their freedom endeavor used the procedures of their trial to memorialize, dramatize, and document the crimes against our people’s humanity. This is a Herculean dexterous task of great sacrifice of ones freedom, but essential to establishing motive for our history and the adherence to international standard.

The reality is in almost all of our political trials. The trial process in the U.S. does not further by design the objective for transitional justice. The best legal practitioners, who remain political naturals in applying the law by necessity use tactics that undermine the intent of the accused political defendant and generally the result is a denial of justice for all political prisoners.

The political prisoners who have been captured and accused, while in general accept being apart of the movement, therefore they accept the responsibility to have a political trial even though it is generally against their attorney’s advice. The process of the trial by its nature means they carry the responsibility of all the charged acts of the political period and whether the prisoners have knowledge or not in this setting the truth suffers and a process for transitional justice is abandoned or worse yet, not realized because in the United States there is no process for political reconsideration resolution. Our aim should be to evolve the process. The state’s propaganda furthers their narrative in characterizing the movement and accused so as to justify the state abuse of power and violation of human rights similar to patterns that existed and used by the “third forces” revealed during the South African Truth and Reconciliation Hearings. In this setting, there are more prisoners of political character and motive who are in prison. This apparatus that has served as the primary tool of the U.S. justice and prison system function in a parallel axis to smother any acknowledgment that exists of internal conflict that require an alternative dispute mechanism not only for relief for our prisoners but healing of the spiritual and physical wounds the survivor of the conflict has endured.

In a so-called free society and great democracy, the battle between truth and justice is ambiguous. The use of the long unjustified and selective sentencing and denial of patrol create a stage that they hope will further the nation’s collective amnesia that will manifest a class of “forgotten” disappeared prisoners and survivors.

That is why it is essential that the freeing of political prisoners and P.O.W.s would be the crucial result of the TRC Amnesty Committee process. In the South African TRC Amnesty Committee Hearings (HRVC) 854 political prisoners were freed through the process, keeping in mind the period of review was between 1960-1992-(4), clearly a period that addresses our needs.

Culture is Political in the Throngs of Oppression

From 1957-1997, the acts of horror carried out against the various groups and individuals of our resistance became the themes of songs, music, and dance, proving crucial to the political mobilization and awareness of the status of resistance and the department of repression.

Culture served the masses of South Africa to become observers of the non-fictional text, highlighting so many survivors with their tales of suffering that they carried alone with the fear that they and their burden may be forgotten. In turn, it was the culture’s tradition to make use of call and response. The natural response and expression that kept the younger generation engaged in the outcome of both the Human Rights Violation Committee (HRVC) and the Amnesty Committee Hearings (ACH). To much of the world, the Truth and Reconciliation Hearing became the theater of anguish of the apartheid system. In the truest sense of the term, drama was a very important tool in the South African success of the TRC.

The task here in the United States as we prepare to pursue a process that distinguishes our situation juxtaposed to South Africa’s, is that our present younger generation is still suffering paramount abuse and trans-generational trauma based on race and class while lacking engagement and dare we say suffers political amnesia while being emotionally and spiritually disconnected. We demand a political process that heals the pain or at least acknowledges the psychological and emotional damage done to past generations that fought a U.S. style of apartheid system which now demands some aspect of resolution and expressing of the specific details of how the abuse was carried out so as to be warned of such tactics for the safety of their future. There can be no parallel to traumatic events that characterize our resistance to oppression and the terror our freedom fighters repelled many times with nothing but the sound of James Brown telling us “To get up and get down”-”Say it loud I’m black and I’m proud.”

There is no other way for us to realize the outline objectives unless we do not gravitate squarely in the gut of this political process with the participation of our hip hop, reggae, and neo-soul artists by creating a collective narrative for the healing process. What can encourage this process is by having respected artists in the grassroots movement writing screenplays, promoting the saga from the history of our resistance. Examples of this include HBO’s SATRC film “Red Dust,” Lucky Dube of South Africa, Bob Marley inspired our support for the nation of Zimbabwe, and Fela Kuti fought for the freedom of Africa. The so-called generational gap and the period of resistance, this amnesia can be closed by the interconnectedness with all of our artists. If the goal is to guide their motivation, hip hop and reggae can influence the upswing of the younger generation. In the Middle East, it is the songs, the beats, the lyrics that, in absent of a leader, articulated the demands and hopes of those who are in search of a better future. We must acknowledge our artists’ role in our resistance and its healing in our political process. The call to go forward should be heard in the lyrics of our hip hop, reggae, and neo-soul artists, specifically for the freedom fighters, political prisoners and prisoners of war, and the tales of resistance and struggle in ire sounds.

This is most important when we see the similarities to the SATRC model in that public hearings would be key to conflict resolution. The past crisis is also about the optic of the theater of conflict where special reports may not read deep into the pain and suffering lacking expression. Even in the post-TRC South Africa, the analysis commission is somewhat cynical of accomplishing its goal. Many survivors know that the climate of their suffering and resistance and sacrifices are memorialized for future generations by their artists.

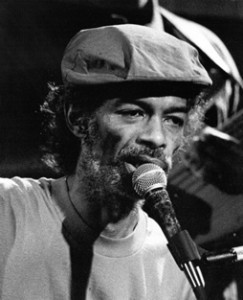

Here in the United States our civil rights/national liberation movement artists are similar to the South African artists of all genres. They too were motivating for our journey into the abyss. To resist, when overpowered, we endured in the face of hopelessness, leading to our older generation and younger generation staying united in spirit because the beat of the drums, the lyrics of our poets, the rhythm of Motown, Curtis Mayfield, James Brown, and Gil Scott Heron. It was Stevie Wonder’s “Happy Birthday to Ya” that pushed for the celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. It was Nina Simone who insisted that we internalized the pain of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. She encouraged us to be strong, and told us to be “Gifted” in her song “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black.” As did Chuck D and Public Enemy when they reintroduced Malcolm X to the “X” Generation with “Fight the Power.”

Here in the United States our civil rights/national liberation movement artists are similar to the South African artists of all genres. They too were motivating for our journey into the abyss. To resist, when overpowered, we endured in the face of hopelessness, leading to our older generation and younger generation staying united in spirit because the beat of the drums, the lyrics of our poets, the rhythm of Motown, Curtis Mayfield, James Brown, and Gil Scott Heron. It was Stevie Wonder’s “Happy Birthday to Ya” that pushed for the celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. It was Nina Simone who insisted that we internalized the pain of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. She encouraged us to be strong, and told us to be “Gifted” in her song “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black.” As did Chuck D and Public Enemy when they reintroduced Malcolm X to the “X” Generation with “Fight the Power.”

Gil Scott Heron told us that the truth of our revolution “Would not be televised.” Gil Scott connected the struggle to the youth with the anthem “What’s the Word” from the song “Johannesburg.” This document does not provide a clear study of the role of our musical artists, poets, and actors in our resistance. Our artists and the hip hop/reggae movement are the tip of the spear that reminds the people of their past and directs them towards the future.

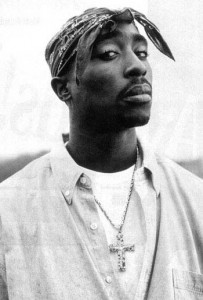

Tupac Shakur, in his song “White Man’z World,” pushed for the release of political prisoners and to bring exiles (like Michael Cetewayo Tabor and Donald Cox) a fair hearing. Tupac, having been raised in the midst of the liberation movement and its culture, was heavily impacted by it and despite the struggles he encountered, he not only embodied the likes of Chuck D, Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, and Gil Scott Heron, he reflected for the next generation why such crucial matters like education and equality should always be striven for implacably when he said in “Words of Wisdom:”

Tupac Shakur, in his song “White Man’z World,” pushed for the release of political prisoners and to bring exiles (like Michael Cetewayo Tabor and Donald Cox) a fair hearing. Tupac, having been raised in the midst of the liberation movement and its culture, was heavily impacted by it and despite the struggles he encountered, he not only embodied the likes of Chuck D, Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, and Gil Scott Heron, he reflected for the next generation why such crucial matters like education and equality should always be striven for implacably when he said in “Words of Wisdom:”

“So get up, it’s time to start nation buildin’/

I’m fed up, we gotta start teaching children/

That they can be all that they want to be/

There’s much more to life than just poverty”

Our effort to put forward a TRC in America that will guide our development for a meaningful structure in order to accomplish our objective will have to be driven with the desire for that political process.

The realization of a TRC for our specific purpose should not be solely an intellectual exercise and forum. Our above stated aim should be to stimulate information about specific events, public debates, and advance the discourse on restorative justice, transitional justice, and alternative dispute mechanisms that will help formulate national policy that should be sponsored by our elected representatives.

While there will be a continual critiquing of the ultimate benefit of the SATRC model, many doubters will prudently alert our movement as to its pitfalls. It should be noted that even many of the SATRC commissioners stress the establishment of their TRC was particular to South Africa’s unique needs. There has been at least 16 TRC around the world prior to embarking on the SATRC model. The commission has admitted that their process was not as organized as the results might indicate as there was no precedent for their specific need. Our North American Truth and Reconciliation Commission will have 38 TRCs from around the world to draw from, however we too will be challenged in respect to expressing the inefficiencies of the courts and civil prosecutions in regards to addressing the disclosure of human rights violations.

The task at hand is creating an atmosphere with a broad enough demand focusing on the civil right/black liberation era which indicates a centric demand while giving respect to both segments of the movement’s sacrifice for our people and abuse suffered by our people. This process should primarily be designed on a negotiated agreement.

Our interest and preference is for a structure similar to the SATRC model because of the result of the amnesty committee that freed 849 freedom fighters. The freeing of political prisoners and prisoners of war of the black liberation movement indicates success. There are also unresolved disappearances of many blacks/non Africans carried out during the civil right era including hangings and terror that has yet to even be discussed. The process that opens the flood gates of the level of human rights violations as apart of the testimony to human rights violations will go a long way in the healing process.

As in South Africa, the exposing of the special squads’ such as the ‘Crowbar’ and ‘Third Force’ police counter insurgent units that operated during the 70s, 80s, and 90s will help set the example in how we sharpen the COINTELPRO disclosure, similar to the role the Goldstone Commission on Public Violence and Intimidation did. The bombing of MOVE in Philadelphia is prime for truth resolution and an answer for why all the children (sans Birdie Africa) had to die.

As so many New Africans of the so-called greatest generation are about to make their transformation, our people owe them their true place in history.

There is a new social, economic, and even political agenda in the so-called “black/New African Nations” progressive social struggle.

The past social struggle is still relevant, but part of today’s progressive social political struggle should be the development of the TRC in order to truly define the political social progression from the past to the present progressive political social agenda which will help build a mass organization to accomplish our objective.

We have waged various levels of political social struggles for progress that included self defense in a highly restrictive and racist environment, being surrounded daily by hostile forces while being outnumbered, being deficient materially, and engaged through low intensity warfare with our priorities being manipulated and disorganized. It is very possible that the North American Truth and Reconciliation Commission process will help define how to tactically and strategically overcome such odds in order to achieve for our future generations the concrete goals and objectives we desire.

The general dependence of our movement on international instruments for recognition in a post-9/11 world is an exercise in wishful thinking.

The Obama era has not seen the U.N. and N.G.O. instruments operate constructively. The process of restorative justice and alternative dispute mechanisms are solutions that are an internally generated apparatus for internal conflict and post-conflict. This new language and structure are becoming part of a resolution tool and culture of the international human rights circle.

There are standouts that will help to bring attention and give our North American Truth and Reconciliation Commission the observation and approval to those inside the international culture. We will have to become self-reliant and creative in building a social movement that will create the conditions we seek. An instructive example is Judge Goldstone, who during the South African Pre-Resolution, was a standout that set the precedent in exposing the abuse of power of the racist illegal South African government’s legal system. Goldstone’s report was the precursor to the implementation of the SATRC. It is important that the foundation of the North American Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s conceptualization of philosophy, theory, ideology, and policy drives the concrete objective, principle, values, strategy, and tactics.

The perpetrator will do all to undermine the process. The broader the base demand for this process that will give both sides an incentive to participate in the process the closer we will be in accomplishing our goal and objective.

This is the age of social media where the tragic dramas presented in testimony to a broad base of the American public will hopefully inform and expose the present generation and future generations to lessons this country need not repeat.

“A revolutionary isn’t born out of something ‘good’” but of “wretchedness and bitterness.” Rigoberta Menchu noted. “Out of suffering comes the strongest of soul” Khalil Gibran once said, and with that, may I remind you that history will judge us by our struggle.

Aim High and Go All Out,

Stiff Resistance,

Dr. Mutulu Shakur

Powerful.